Words on walls “haq al-shuhada fi raqabatina” The martyrs’ right are on our neck Plaque 94 “matinsuuch haqqui” Don´t Forget my right Plaque 93 “iw’u fi huugat al-kalaam… damm al-shahiid tinsuh “ In the midst of the bursting words, don´t you ever forget the blood of the martyrs.” Plaque 91—- Extracted from Maliha Maslamani Graffiti of Egyptian Revolution, Arab Centre For Research and Policy, 2013, pp. 90-91.

Al-qassas al-qassass darabu ikhwatna bil russass Avenge, avenge the martyrs; they have shot bullets on our brothers and sisters. Haq al-shuhada lissah magaash, damm al-shuhada mish bibalaash The right of the martyrs did not arrive (was not collected); the martyrs´ blood is not for nothing. “Ya nigiib Huquhum ya nimuut zayuhum” We either get their right (blood) or die like them —- Slogans chanted in the streets

Image by Mona Abaza

Introduction

I would like to focus in this piece on the multiple and nuanced ways in which martyrs and martyrdom are represented in the blossoming Cairene graffiti and how these instigated deep sentiments as iconic displays in public spaces. More specifically, how through time these representations have been undergoing transmutations, taking different meanings and shades because of different valuations, which have been affected by political and class factors. I will equally address the unresolved paradox of the increasing interference by actors of the international art market inevitably fostering the commodification of “revolutionary art”. I have started since 2011 to systematically take photographs of the graffiti of the Mohammed Mahmud street, which is one of the main streets leading to Tahrir Square. The article unfolds the political events in relationship to street art until end of May 2012, just before the downfall of Morsi in July 2013.

Martyrs, Picture taken at the Mohammed Mahmud Street/ Image by Mona Abaza

Having said that, I would like to commence this article with a recent unforgettable incident much revealing of the growing significance of graffiti as a powerful subversive instrument against the former authoritarian regime of the Muslim Brotherhood which was ousted in July 2013. In March 2013 a member of the Muslim Brotherhood slapped in the street a female activist who was participating in drawing graffiti about the martyrs of the revolution, exactly when there were rumours about members of the Muslim Brotherhood meeting in their headquarters. The confrontation led to violent clashes between the anti-Muslim Brotherhood revolutionary activists and the militias of the Brotherhood, which took place opposite of the headquarters of the party in the Muqattam area.[i] Very quickly the clashes escalated into a violent street fight that resulted in the wounding of a few protesters. This was certainly not the first time that confrontations between the Islamists and the revolutionaries led to violent clashes. As benign as an act of drawing in the street might seem to be, it upsets the long tradition of authoritarianism. The Mubarak regime, the SCAF (the Supreme Council of Armed Forces which ran the country for almost a year and a half after the ousting of Mubarak), and the movement of the Muslim Brotherhood are all united by the repulsion of such a public act, simply because it is undertaken by the rebellious youth. Undeniably, there is a long tradition in the West of labelling graffiti as vandalism. However, in the current Egyptian context graffiti takes on an even more dramatic twist. The humiliating act of slapping a young female activist retells the story we all know, that graffiti is time and again regarded as an insulting affront to the patriarchal ruling class. It reveals that nothing has really changed since the ousting of Mubarak, followed by the rule of SCAF and then the Muslim Brotherhood. All three groups abhor not only graffiti, but also public performances and dance. Take for example the fashion of the Harlem Shake dance (perceived as utterly indecent by the Islamists) which was performed in March 2013 in front of the Muslim Brotherhood headquarters in the Muqattam area. The performers/ protesters used a mass-culture globalised trend and turned it into a form of protest, or rather a public statement of insolence; an affront to the double morality and mediocre performance of the Islamists. [ii] A large crowd of young men and women gathered in front of the headquarters to dance wildly, while some of the protesters masqueraded by wearing a Mickey Mouse mask and white gallabeyyas (the long traditional white male robe) to ridicule the Islamists’ garments and style. Others carried a tire or wheel as during the presidential campaigns Morsi had been nicknamed the spare wheel (al-stibn). Needless to say, the Muslim Brotherhood denounced all these public performances as destabilizing, disordering and chaotic acts. Notice here how important the space of the Muslim Brothers headquarters in Muquattam had become a space for public performance.

Clearly graffiti artists have drawn- and continued to draw – the strong analogy between Mubarak, the SCAF, and the Muslim Brotherhood for being one and the same continuing mode of rule. The artists wanted to convey one main point: nothing has changed. The revolutionaries have not spared any of these three groups from biting insults and hilarious sardonic humiliating drawings. The walls powerfully and visually narrate and challenge the continuity of authoritarianism with its multiple facets. Insults and sardonic comments and drawings thus have come to be directed against the two most sacred and previously untouched spheres; the established patriarchal army and religion, or rather the so-called stakeholders of religious morality, i.e., the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis. Simply put, if there is one thing in which the revolution has succeeded it is the debasement of the sacred gods through mockery.

As Egyptian authorities keep erasing the art by whitening the walls, artists have responded with elaborated and sometimes improved versions of the previous paintings, until they excelled at the art of resisting, challenging, and insulting the counterrevolutionaries, the wielders of power, and their allies. Colloquial Arabic was often prominently displayed on the walls, and no one within the centers of power was spared from mockery. The internal security apparatus, the SCAF, the associates of the former regime, Muslim Brotherhood leaders, and President Morsi – all got their share of insults and satire.

Al-ikhwaan khirfaan (The brotherhood are sheep) was one main slogan that has multiplied all over the walls, which was often accompanied with plenty of tamed white sheep. Dustuurhum ghair dusturna (Their Constitution is not our constitution), Dustuur al-ikhawan Baatel (The Muslim Brotherhoood’s constitution is invalid). Morsi has been portrayed in graffiti as a hand puppet, as a thug, as a liar displaying his chest (alluding to his performance during his first speech after becoming president when he bared his chest to the crowd at Tahrir Square to show that he is one of the people and does not require a bullet-proof vest), or as the queen of clubs card being manipulated by a bigger evil looking joker. No wonder then that the current regime, much like SCAF, feels extremely threatened by such sardonic public displays.

Let us take for example the famous half-Tantawi-half-Mubarak portrait that first appeared at the corner of Mohammed Mahmud street during the early days of the revolution. Since the image has reappeared in different guises. Repertoire here might perhaps be one key concept that can help explain why the regular use of violence by authorities, and the recycling of the old regime’s discourses by the perpetrators of such violence have become dominant elements in the apparent counter-revolution led by the Muslim Brotherhood. For example, the Brotherhood has been repeatedly nicknamed mockingly as the new bearded Mubarakists. Not only did they utterly lack imagination about the sort of program or governance they aspire to achieve, but as ex- victims, they seem to be primarily keen on badly mimicking their former victimizers. The Brotherhood seems to be unable to liberate itself from the script assigned by their former suppressors. That is why they were caught in reproducing identical corrupt mechanisms and twisted acts culled on the previous ruling NDP party by manipulating and rigging the elections. That is why too, they were perpetrating forms of brutality and blatant violation of human rights on a much higher scale, so much that the running joke now in Cairo was the following: Mubarak has turned to be a gentleman compared to the current rule of Brotherhood and its militias that spread terror and committed murders in the public sphere. The Brotherhood´s hunger for purchasing real estate, super markets and capitalist enterprises coinciding with the way they were desperately trying to grab the entitlements of the state is simply shameless. As if the obvious farcical repetition of history needs no commentary. Repertoire might explain too the insistence of revolutionary artists to repaint the same murals time and again. Through the concept of repertoire, one can view the corner (where Mohamed Mahmoud Street meets Tahrir Sqaure) as the site of an unfolding continuous dramaturgical performance that visually narrates the history of the revolution.

The portraits, which were produced by rabitat fanani al-thawrah (“The association of the artists of the revolution”), kept on being erased on a regular basis, presumably because the government must have felt utterly humiliated by such a negative portrayal. Yet despite successive attempts by Egyptian authorities to erase the paintings, the wall never stayed empty for more than a few hours before it was repainted with the same images, usually with more detailed additions and variations. It is interesting to note that the same graffiti was later replicated on the walls of the Itihadiyya presidential palace in Heliopolis after the eruption of the massive demonstrations against Morsi’s controversial constitutional declaration, as well as the constitutional referendum that was hastily convened last December 2012. In a picture I took of the half-Mubarak-half-Tantawi portrait in March 2012, above the painting one finds the words “The revolution continues.” The statement at the bottom reads illi kallif ma matsh, meaning “one [i.e., Mubarak] who has delegated authority to someone else [i.e., Tantawi] has not died.” This phrase rhymes with the popular saying illi khalif ma matsh, or “one who produced off-spring has not died.” Below the phrase is the following sentence: “A [military] council of shame and a lying Field Marshal.”

Portraits of presidential hopefuls and former Mubarak aides, Amr Moussa and Ahmed Shafiq, were later added to the same painting. To the left of the image is a statement that reads: “I will never grant you any trust; you will not rule me one more day”. Subsequently, in September 2012, the wall was once again erased, the half-Mubarak-half-Tantawi portrait was repainted in a smaller size, with the addition of a portrait of Muslim Brotherhood General Guide Mohamed Badie. Below it is an image of a painter using his brush fresh with dripping paint as a weapon in confronting a policeman’s stick. A poem at the bottom reads:

Martyr Mohammed Serry, Picture taken in Mohammed Mahmud Street 11.09.2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

- “You, a regime scared of a brush and a pen

- You were unjust and crushed those who suffered injustice

- If you were honest, you would have not been fearful of painting

- The best you can do is conduct a war on walls, and exert your power over lines and colors

- Inside you are a coward who can never build what was destroyed

Performative Graffiti

For the past two and a half year, the attempt was to record a chronology of the changing graffiti of one street, the Mohammed Mahmud Street that has witnessed various clashes and confrontations between the police forces and the protesters. The same street also witnessed a constant erasure and whitening of the walls by both the authorities as well as painting over previous drawings by the graffiti painters .[iii] Much attention has been drawn to the mesmerizing appearance, disappearance, and reappearance of the numerous faces and portraits of the martyrs of the revolution on the walls of the city of Cairo. My interest is not confined to graffiti as a vibrant form of street art but extends also to the interactive and “performative” encounters of various publics with the walls that visually narrate the dramatic events that happened in the street.

A long-term project aims to closely analyse the interactive element that brings together protesters who experienced death during horrific moments in Mohammed Mahmud street in 2011 and 2012, the street’s residents who were looted and caught as prisoners in the urban war zones and suffered from permanent lung and health diseases after much lethal gas was spread all over the area. After the February 2012 Port Said massacre of the fans of the Ahli Ultras, even more publics came to interact with the space of the street after the appearance of many new martyr portraits on the walls. The street was transformed into a memorial space, a shrine (a mazaar) to be visited and where flowers could be deposited.

Zoning the City and Graffiti

The construction of concrete walls in downtown Cairo by the army made life practically impossible for many during the last few months of 2011 and in 2012 and continue to be until today. The Qasr Al-Aini cement barricade was particularly obstrusive. Half of the barricade was pulled down in April 2012 by protesters, while a roughly one-meter-high wall built of solid cement-blocks still remains. The scene in May 2012 was surreal. The adjacent barricade that blocked the neighboring Sheikh Rehan Street remained in place, so that athletic young men and women have increasingly made it their daily routine to climb the several-meters-high wall from both sides.

In essence, the city has become compartmentalised, by the erection of barriers, barricades, barbed wire, tanks and militarised zones. The barricading – the creation of a buffer zone between protesters and police – first began in November 2011 on Mohamed Mahmoud Street. The military and police thought it could resolve the confrontation with protesters by erecting wall after wall. By doing that, they not only rendered mobility impossible, but also made everyday life in areas adjacent to Tahrir Square almost unlivable.

In the morning, numerous buses lined up in front of the two walls. Most probably, these vehicles transported the hordes of employees and workers back and forth whose offices are located in the area.

Then, the most striking scene: hundreds of male and female employees and pedestrians who must climb a single ramp every day in order to traverse the one-meter-high barricade before climbing down another ramp to reach the other side en route to Tahrir Square. Then, if you walked along the fence of the nearby American University in Cairo, you will find the fantastic painted murals of artist Alaa Awad, which have now been supplemented with chairs and tables to become the newly-conquered open-air café on the corner of Mohamed Mahmoud Street and Tahrir.

Those sitting there appear to be enjoying themselves while meditating on the chaos of Tahrir traffic jams and the mushrooming of tents in the square and in front of the iconic Mugamaa building. You ask yourself: Why is it that the barricades have remained in place since December 2011 as if trouble was still expected by the regime? Or was this yet another example of the Egyptian proverb Dawaakhini, ya limounah –(literal translation: make me drowsy lemon, meaning intentional merry go round until total exhaustion) a merry-go-round tactic aimed at inducing fainting so as to make life impossible for the capital’s citizens?

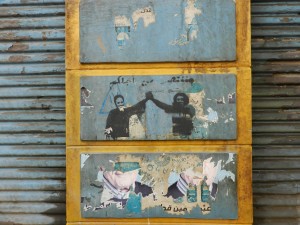

Picture taken at the Mohammed Mahmud Street, 13 November 2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

In fact, Cairenes are all too aware that the entire area around Qasr Al-Aini Street, including the Ministry of Interior, is a militarised zone to be avoided by any sane person.

And the remaining walls – with the exception of the Mohamed Mahmoud Street barricade, which was removed in February 2012 – continue to exist, albeit covered in graffiti that keeps expanding by the hour.

The blocking of Qasr Al-Aini Street, a vital Cairo artery, has made normal perambulation in downtown impossible. It appears as if the powers that be have a master plan to torment all the capital’s denizens – pedestrians and car drivers, rich and poor (this is democracy) – via the tactic of “detouring.”

It’s as if the entire city was exhausting all its time and energy to find the shortest passable way between two points, not to mention finding a single straight street that might be used from beginning to end without being subject to detours. The observer of this new urban constellation can immediately discern different interrelated phenomena. On the one hand, there’s an emerging subculture of protest; on the other hand, it’s interesting to note how resourceful drivers have become in finding alternative routes to their respective destinations. Last but not least is the emergence of an informal economy – street vendors, etc. – with its marginalized population that has gained a new public visibility. This is happening not only in Tahrir, but also on the bridges and other areas previously policed by security forces.

Then, from March until September 2012 Mohammed Mahmud street turned into a highly mediatised space when a different crowd of graffiti painters occupied the street. Some of the painters looked like they were performing to be photographed by the media. Then once again, numerous passersby interacted with the street by either taking pictures or by posing in front of the walls. Often too passersby had the urge to share a few words with other passersby, the street children, the homeless and the vendors who squatted for consecutive months.

Martyrs: Mina Daniel and Sheikh Emad Effat captured 12 April 2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

Confrontations erupted at Tahrir Square several times, and once again in November 2012 during the commemoration of the first Mohammed Mahmud incidents.[iv] The clashes in turn resulted in a banner being suspended at the entrance to the street with the following words “No entry for the Muslim Brotherhood”. Graffiti continued to be altered at an amazing velocity even after Morsi became president. Simultaneously, more concrete walls were erected all around the area of Kasr al-Aini, around the Ministry of Interior, and the Simon Bolivar Square, as if there were no difference between the military rule and the Brotherhood (see Abaza 2012). This said, after January 2013, not only Mohammed Mahmud street but the entire area suffered from much devastation and looting. On top of that, the historical building of the Lycee school caught a huge fire in November 2012 so that the street today looked like a deserted ruin. This certainly has affected the graffiti movement, which has slowed down since January 2013. Whether it will pick up once again is difficult to predict at this point.

Over the course of the past year, graffiti painters brought to the wall conflicting opinions, discourses and struggles. The walls moved through various stages and metamorphoses, as if determined to follow the unfolding events. The representation of the martyrs has not been spared from these wars over the walls. However, the same martyrs kept on being represented in multiple ways with shifting priorities, preferences and styles in iconic representations.

Obviously, not all martyrs are commemorated equally, much like human lives and deaths seem to be evaluated differently. That is why human rights activists have been doing the heroic work of searching for numerous unknown and disfigured corpses in the morgues, mostly the poor unknown and missing. Once again, the nation was shaken when hearing how Omar Salah, a twelve-year-old child and a poor ambulant seller of sweet potatoes in Tahrir, was murdered with two bullets.[v] It was discovered later that he was shot by a soldier who targeted him, while in the media it was announced that he was shot by mistake. Had it not been for the tedious work of human rights activists in the morgues, Omar Salah´s death would have passed as an unrecorded incident.[vi] Only recently, his portrait appeared on Mohammed Mahmud street.[vii] If I am not mistaken, since his death, there has been only one portrait of Omar on Mohammed Mahmud Street. This illustrates how that class differences affect the making of the iconography of the revolutionary martyrs.

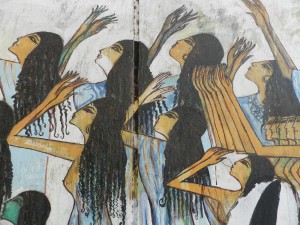

Nevertheless, despite these hierarchies and continuous erasures, the martyrs continue to occupy a prominent place on the walls of Cairo, as the main subject matter in the graffiti. Another prominent subject matter concerns gender issues, such as sexual harassment or the so-called blue bra incidents. Gender also figures centrally in the iconography of martyrdom itself, which explains why graffiti is drawing so much the attention of feminists. For example, the long Egyptian tradition of funerary rituals, of mourning and excessive weeping, or what could be called a local culture of death, mainly perpetrated by women, is wonderfully depicted in the murals. How many times have I heard that the revolution will be completed by the numerous mothers of the martyrs that are growing by the day. The mothers of the martyrs keep on appearing and reappearing on the walls. Gowayya shahiid, Inside me is a Martyr by Heba Helmiis among the most recent publications on graffiti, once again dedicated to the martyrs of the revolution.[viii]

Ammar Abu Bakr ´s Narrative of the Martyrs` Portrayal

Ammar Abu Bakr is considered a rising star in the Cairene graffiti scene. He holds a teaching position at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Luxor University, and he was amongst the earliest artists to occupy and paint on the walls of the street precisely during the most violent confrontations. Numerous youtube videos, interviews, and round table discussions have been focused on Abu Bakr’s activism and his vibrant participation through his art in Mohammed Mahmud Street. There is a significant crowd of photographers and bloggers who have closely been following and writing about both Ammar Abu Bakr and Alaa Awad´s graffiti (explained below) all over the city. Meanwhile, Ammar Abu Bakr has also gained international recognition and has repeatedly been invited to Beirut, Berlin, and other places in Europe. to give talks and exhibit his work. Abu Bakr first became known through painting the mutilated, one-eyed victims of the first Mohammed Mahmud incidents of 2011. He also painted one of the two buraqs on the walls of Mohammed Mahmud Street in 2012, which appeal to at revived symbols of popular culture and Islamic tradition.[ix] Together with Alaa Awad, another art instructor of Fine Arts at Luxor University, he painted the epical mural of Al-wassiifaat/ the Hostesses, which was erased during the latter half of 2012. [x] The murals produced by Alaa Awad, Ammar Abu Bakr and Hanna El-Degham were painted instantly on the day following the Port Said massacre on 2 February 2012 massacre. They are the reason why the street has turned into a well-known memorial space of the martyrs.

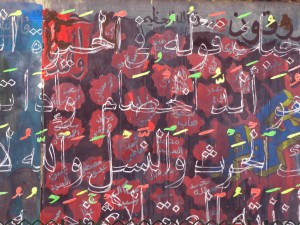

Calligraphy. Verses of the Quran by Ammar Abou Bakr Captured 13 November 2012, Mohammed Mahmud Street/ Image by Mona Abaza

Alaa Awad ´s “hostesses” reveals how a feminine archetype derived from the Ancient Egyptian tradition, symbolizing Egyptian beauty and refinement, has become a powerful force in confronting the SCAF. Here the SCAF is depicted as a huge long snake that extends over the top of the gate of the Lycée School on Mohammed Mahmud Street. The snake´s head consists of three joined heads of generals. Ammar Abu Bakr drew the snake with the three generals’ heads. As part of an ongoing dialogue, Alaa Awad then responded to Ammar Abu Bakr´s mural by saluting (and confronting) the generals’ heads with the ancient Egyptian hostesses. Awad meant to portray a centuries’ old feminine wisdom facing the brutality of SCAF with a welcoming smile. Once again, Pharaonism inspired Alaa Awad who inserted demotic writing, separating the two drawings. Seven cows now stand behind the hostesses. Awad defines these as the seven Gods of Hathor, or the seven heavens symbolising fortune, joy, femininity, goodness and most important a brighter future.

Then the mothers of the martyrs graffiti to the mural of Mohammed Mahmud Street by Ammar Abou Bakr toward the end of May 2012. Abou Bakr painted it not long after Alaa Awad had demanded from the American University in Cairo administration to “fixate” the walls in order to protect them from erasure. Abou Bakr, being a hard liner, was from day one against the idea of ‘fixating’ any of the murals. He insisted that graffiti ought to remain ephemeral and changing. Graffiti should remain a street art that narrates the unfolding and unfinished events of the revolution. It should never be gentrified through the manoeuvres of the art market. Since the murals are to be considered the barometer of the unfolding events of the revolution, they should be constantly alternating. Abu Bakr painted the mothers of the martyrs over the existing and yet fascinating work of Alaa Awad called Al-Naaehaat or the Mourning Women. For some, it looked as if Abu Bakr was intentionally trying to destroy Alaa Awad´s earlier mural displaying the Port Said martyrs, which he completed immediately after the February 2012 massacre.

Alaa Awad´s Al-Naaehaat or the Mourning Women of ancient Egypt, is a scene of a funeral depicting ancient Egyptian women accompanying a sarcophagus symbolizing the death of the Ahli Ultras football youngsters who were massacred in the stadium of Port Said. Demotic writing appears a few meters away. Once again according to Alaa Awad,[xi]up to the present the persistence of ancient Egyptian mourning traditions is to be still witnessed in Upper Egypt. Mourning women perpetrate identical Pharaonic customs, such as tearing clothes, shaking the bodies hysterically, weeping excitedly and smearing bodies and faces with mud to let sorrow out. The muses on top of the mural are receiving the ascending souls of the martyr. The tiger is the symbol of anger for the 75 young martyrs, who died in Port Said. The women are carrying black Lotus flowers, a sign of great sorrow.

This said, had I not interviewed Alaa Awad personally, I doubt that I would understand all the references in both his Al-Naaehaat or his wassiifaat murals. The murals cannot easily be deciphered by lay people in the street. I have thus asked myself why it is that his murals are so appealing. Is it simply because they remind us of touristic postcards of Pharaonic temples? I often wondered whether, had I not interviewed him, I would have been able to draw the connection between the ancient Egyptian funeral rites and the Port Said massacre. It seems that Alaa Awad´s emphasis on ancient Egyptian themes and his overemphasis on the “turath” (heritage) seems to be fitting with the trend of commodification in the international art market in which the need for ethnic and national classifications is part and parcel celebrating exoticism. Would it thus be a coincidence that Alaa Awad´s work has been immediately recuperated by the established “gatekeepers” of the art market and his entire murals have been reproduced for display in galleries?

Abu Bakr’s mothers of the martyrs, was painted over Al-Naaehaat around April or May 2012. It portrays a staring woman who displays the photograph of her deceased son. The graffiti is a stencil derived from a photograph that is depicting the numerous mothers who protested endlessly for the trial of the killers of the martyrs. Abu Bakr composed huge letters stating “Forget the past and stay with the elections.” This is a bitingly ironic statement that attacks the entire procedure of elections (which led to Morsi becoming president) as well as those believing that elections could be the solution to circumventing a junta. Abu Bakr’s words convey the idea that elections are merely a bluff to divert citizens from the martyrs and the twelve-thousand incarcerated under military rule. The Mothers of the Martyrs was once again erased in the summer of 2012.

Ammar Abu Bakr grew up in a middle class family in Minya, in Upper Egypt. He recalls quite well how the internal security forces have for decades been perpetrating brutal methods of repression against the Islamists in the region, by not only humiliating and torturing them but also by prosecuting entire families, including denuding and sexually assaulting women. It was as if a long history of vendettas (again according to Abu Bakr) had already existed for many decades between the population and the police forces. Two of Ammar´s uncles turned into hardcore Salafis. One of his uncles even ended up in Afghanistan to work with the al-Quaeda organization. When his uncle returned from Afghanistan, he was arrested. Ammar evokes with great emotion the first encounter with his uncle after he had disappeared for many years. That encounter took place during the first Mohammed Mahmud incidents of 2011 when Abu Bakr found himself in the camp of the revolutionaries confronting violently the Islamists. Abu Bakr was confronted with a violent physical encounter with his uncle who was siding with the police forces in a battle over who is to appropriate the street. It was for him a memorable incident that showed how suddenly, after long decades of brutal state repression, his uncle had changed camps and sided with exactly those in power. This is what made Ammar Abu Bakr even more determined to reflect on how to reclaim religious and popular symbols and most importantly Arabic calligraphy which according to him appeal to the masses.

This said, Abu Bakr believes that the representation of the martyrs in itself was not spared from the bitter struggles, political fights, and bargaining among various competing political factions, exactly over which martyrs are worthier and whose political faction ´s martyrs should be filling the largest space. Or the fact that some portraits of the dead, after continuous wall erasures, kept on growing in size through time. Similarly, the 6th of April Movement invented the idea of leading the marches with huge flags displaying the iconic martyrs (Emad Effat, Khaled Said, and Mina Daniel), as if their portraits were becoming increasingly magnanimous through time. Once again, Abu Bakr refers to the example of the fans of Ultras Ahli who seem to be prioritizing their martyrs over others. This is mostly noticed in the growing expansion in the size of the portraits as is the case of the 74 martyrs of the Port Said massacre painted all around the fence of the Ahli club on the island of Zamalek, of which some have already been erased. The huge staring and naively painted faces of the young martyrs provide an impressive effect of how death does not spare youth. But, as Abu Bakr points out, they simultaneously erase, or background, other martyrs.

Abu Bakr believes that iconic martyrs like Mina Daniel (killed in Maspero in October 2011) and Sheikh Emad Effat (killed in Mohammed Mahmud in 2011) have been utilised at various times by “infiltrating” painters who might have been encouraged by the “fulul” (ancient regime class) for different agendas that had little to do with revolutionary political activism to once again play with the highly timely and sensitive issue of the martyrs.[xii]

Once again, martyrs Sheikh Emad Effat and Mina Daniel, Captured 9. 02 2013, Mohammed Mahmud Street/ Image by Mona Abaza

Following this line of argumentation, Abu Bakr firmly believes that, after a long struggle in the street, graffiti has been used and abused by various actors. It has been commercialised and commodified, precisely through the growing interference and agendas of international funds, organizations, cultural centres, curators and the so-called ‘gate keepers’ of the art world as well as the media coverage which offer programs and propose spaces through funds for celebrating street art, music and artistic expression. The trend aspires at co-opting street art by taming it through exhibiting graffiti in galleries and in safe spaces like empty garages in the downtown area sponsored by once again curators and foreign cultural centres. [xiii]Abu Bakr insists that there is an obvious difference between the graffiti activists who were drawing on the walls during the violent Mohammed Mahmud events of November and December 2011 and what unfolded later. The point he raises is: why graffiti and for what purpose? ‘Being present’ in the street during the height of the urban wars meant to be one crucial way of defending the space from the attacks of the Muslim Brotherhood who were siding with the police forces. It was a way of supporting the street fighters through narrating visually the battles on the spot. This political posture was meant to be different from what unfolded afterwards when another crowd of pseudo graffiti painters (once again according to Ammar Abu Bakr) with naïve attempts at excelling at the rigid styles they had learned in the local art academies, appeared in the streets after the urban wars were over. Similarly, one sees even more commodification in media talk shows, through the overemphasis on the images and through the explosion of paraphernalia sold around Tahrir Square and downtown. This seems to be going hand in hand with an emerging trend among some real-estate capitalist investors in the centre of town (wist al-balad) who have begun sponsoring art and graffiti artists as one way of revamping downtown. It is one way to end up perhaps in what Sharon Zukin (1996:135) has termed the growing capitalist control of the “symbolic economy” of the city, a trend, which started in the seventies in the US. Here investing in art becomes a forum for gentrifying public spaces and a way of manipulating violence, ultimately creating a new wave of a “culture industry” highly dependent on financial capitalism. Graffiti might not be spared from such manipulations.

Martyrs Sheikh Emad Effat and Mina Daniel, Captured 11 February 2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

Variations in Martyrdom

We are entering the third year since the January 2011 revolution occurred. Since then, numerous massacres, killings, and obvious violations of human rights were perpetrated by the army and continue to be perpetrated in an even more brutal manner under the Islamist government of Morsi. [xiv] The toll of deaths, of mutilations, of disfigured protesters and of gang raping of female protesters has been frighteningly on the rise since the Muslim Brotherhood came to power.

This is going on parallel with a mesmerizing public culture of protest through well organised marches and demonstrations, violent confrontations, and violent urban wars. Egyptians are today confronted with an unprecedented escalating violence that is building into a “collective trauma” over how to come to terms with the frightening number of very young victims, of mutilated bodies, and even more of blinded protesters. A collective trauma, which has resulted in that today mourning mothers, who have lost their children, are gaining public visibility in the media by the day. Thus, martyrdom is becoming a public concern. It is no longer the poor man’s concern, since violence and murders have touched upon middle class children. This is no novelty, since Khaled Said, the good looking middle class young Alexandrian, was turned into the iconic martyr exactly because of the diffusion via internet of his face, tortured and fractured by the police officers; this face is what triggered the revolution.

Iconic martyr Khaled Said, whose killing triggered the 25 January revolution. Captured 13: 11 2012 Mohammed Mahmud Street/ Image by Mona Abaza

Pain to injury was added since none of the officers responsible for these killings, have been convicted. The trials of the most dramatic violent incident of the “battle of the camel” on 2 February 2011, the major incident that resulted in Mubarak’s ousting, took a farcical twist to once again rescue the culprits.

This explains why there is a kind of perseverance in the act of commemorating the martyrs, collectively, in a multiplicity of ways, through displaying large size photographs of the tortured and dead bodies such as those of the protesters who were brutally tortured at the Presidential Palace in Heliopolis in December 2012. A large number of these photographs have been displayed in Tahrir Square and in the marches. To the contrary, Morsi continuously praised the efforts of the officers when they continued in crescendo to display brutality, while 21 civilians were sentenced to death for the Port Said massacre.[xv] This has left the street with mounting anger growing by the day. Al-Quassaas, justice for the blood of the martyrs, remains thus the major unfulfilled demand of numerous parents and friends of martyrs.

Captured in Tahrir 8 December 2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

Christine Gruber’s work on the Museum of the Martyrs in Tehran is highly resourceful by providing a novel reading in deciphering the way the living in Egypt are handling the unresolved issue of brutal unjust death and martyrdom. Gruber (2012:69) argues that the Martyrs’ Museum in Tehran has turned to be a fascinating space that induces “ritual activity” through creating spatial settings that instigate sacrality. The museum triggered in a way a sacred space “in which visitors engage in communal acts of remembrance and mourning, thereby uniting them into a civic body”(ibid. 68). Furthermore, Gruber tells us that modern museums became producers of collective memory as well as “marketing devices for inciting nationalist pride” (ibid. 69). Gruber´s reading of the multiple functions of the museum could well apply to the emerging forms of public art and the iconic war zone of Tahrir Square and Mohammed Mahmud Street in that it gained a new significance in the collective consciousness as a memorial space.

The Museum of the Revolution in Tahrir Square captured 2 December 2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

“The ritual activity” in relation to mourning is similarly traced in the space of Mohammed Mahmud street through depositing flowers, through filming and being filmed, through hanging on the wall a Quranic plaque, and writing Quranic verses opposite to the martyrs, through displaying the photographs of the martyrs that appear and disappear time and again, through writing poems, insults or jokes. The wall of the American University in Cairo in Mohammed Mahmud Street has become iconic by constantly appearing on television, especially on private ONTV channel as symbolizing the stage of the ongoing revolutionary events, so that the epicenter has shifted from Tahrir Square to Mohammed Mahmud Street. The wall has turned into the new Mecca of foreign tourists.

Remembering the Martyrs then, occurs not merely through the graffiti, but also in the other forms, such as by erecting a memorial obelisk at the centre of Tahrir (in January 2012), which carried the names of the martyrs, but which unfortunately quickly vanished away. The martyrs were once again commemorated by creating an open museum at the “saniyya”, .i.e., the centre of Tahrir. A tent and wooden stands were supervised by a man who distributed pens and paper to visitors. Then, all the visitors of the museum were invited to write wishes, to display the photos of the disappeared, to add flowers, poems and photographs and to write about their future dreams. The open museum was replicated at the Presidential palace in Heliopolis after demonstrations in November and December 2012 . Both museums disappeared after the recurrent violent attacks on both places (Tahrir and Heliopolis). Throughout 2011 and 2012 fantastic instant public installations with coffins, gas-masques, and photos of the martyrs, stating how cheap young lives were given away, appeared and disappeared in Tahrir.

Then after the Port Said massacre, a large billboard appeared on top of the entrance door of the Ahli Club in the Zamalek island. In the middle of the billboard, a large script of the number seventy-two was encircled by the photos of the seventy-two martyrs who were massacred at the stadium. Then, the fences all around of the Ahli club were repainted by huge impressive portraits of each single martyr. One more mock street plaque appeared with the street number seventy-four as a statement perhaps that two more missing martyrs were to be added.

Billboard for the martyrs of the Port Said massacre of the Ultra Ahli fans at the entrance gate of the Ahli Club, Zamalek island. Written on top “We will not forget you”. Captured 8 February 2013/ Image by Mona Abaza

The revenant martyrs are represented in a multiplicity of ways. Often in the form of repertoires, with the sentence that keeps on appearing and disappearing with the graffiti, “Glory to the martyrs” al-magd lil shuhada` and al-Quassaas, to avenge the blood of the martyrs.

Through these repertoires a kind of a conversation with the martyrs is meant to be engaged. For example, underneath the portraits the following sentence appears “ I pray God, may you be happy where you are”.

Clearly then Khaled Said, killed in Alexandria, Azharite Sheikh Emad who was killed in Mohammed Mahmud Street, and Mina Daniel, a Copt killed in the Maspero events in October 2011, have turned to be iconic heroes who keep on appearing and reappearing in multiple metamorphosed ways. Often, too, all the martyrs are lined up on a canvas that keeps on growing, while martyrs are added as time goes by. Underneath each martyr, the date and location of the incident is written (the Battle of the Camel, the Friday of Wrath, 28 January, majlis al-wuzara, Maspero and Port Said massacres). As if one could draw entire galleries filled with ever increasing portraits of the dead.

Near the gallery of the deceased, my camera caught once the following poem:

Mock street name: 74 Street of Martyrs followed by the portraits of the martyrs of the Port Said massacre of the Ultras Ahli fans all around the fence of the Ahli Club, Zamalek island. Picture captured 29 March 2013/ Image by Mona Abaza

I am the martyr

I, whose blood was spilled on every inch here

I, who gave up his life so that you live here

You killed my dream and sold cheaply my blood

And acquitted the killer and did not acquit me

I

I am the martyr

— Signed Picasso 3/6/2012

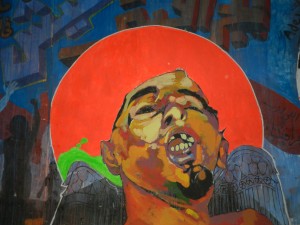

The depiction of the martyrs as winged angels is recurrent. The murals of the Ahli Ultra fans that were drawn immediately after the massacre in Mohammed Mahmud street were filled with many angels dressed in short and ultra Ahli outfits. Graffiti artist Keizer has recently obtained much attention from the international media for his powerful images combining direct and witty slogans. His topical sardonic portraits of former pro-Mubarak Minister of Antiquities Zahi Hawass were accompanied with statements such as “the traitor to the pharaohs”. His jokes are short and to the point, needing no further commentary. The powerful and heart-breaking drawing of an anonymous martyr in the form of a winged angel stands in stark contrast to the previous three graffiti drawings. It appeared on the wall of the Ahli club in Zamalek, following the Port Said massacre. Kaizer complements his graffito with the following sentence: “The meaning of life is that you give it a meaning”.

Captured 06. June 2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

Often too Quranic verses are accompanying the portraits. After the November 2012 incidents a black marble plaque was added at the corner of Tahrir Square and Mohammed Mahmud Street. Ammar Abu Bakr painted last November 2012 a large wall filled with impressive calligraphy of Quranic verses as a statement that Quran and Arabic calligraphy ought not to be the monopoly of the Islamists.

The numerous victims of the fans of Ultras Ahli of Port Said and young martyr Gika killed on Mohammed Mahmud Street in 2012 all appear, disappear and reappear on the walls as if they were repertoires. Sheikh Emad Effat and Mina Daniel keep on appearing as pairs in multiple drawings. Sometimes they are holding each other`s hands, smiling in a position of victory. Here too one notes the size of both Sheikh Emad Effat and Mina Daniel kept on growing over time. Often their portraits are juxtaposing each other. They symbolise Egypt’s religious unity as the Azharite Sheikh and young Coptic activist are united by martyrdom. The Mohammed Mahmud street is full of small stencils as well as huge portraits of both of them. The most recent portraiture of both shows them as if they were flying in the blue sky; underneath are black bodies depicting the struggles and wars. Later, underneath the two portraits, numerous red hands were added alluding to blood and torture. The lower part of that painting kept on changing several times. Policemen and a dead or wounded body carried by two persons have been added. Details continued being added through time like for instance a white ghost holding the two martyrs’ hands. He later was replaced by a white flag on which is written “who is next?”

In November-and December 2012 the wall was once again repainted, portraying more martyrs and Khaled Said’s smashed, destroyed face appearing against a red background with a long series of disfigured martyrs. [figure4] This series is remarkably powerful, or rather chocking through accurately conveying the destroyed and tortured young dead bodies. It was drawn by Ammar Abu Bakr. On top of the portraits is written: “If the picture still needs to be made clearer, Sir, then the reality is even uglier”. Ammar Abu Bakr told me that Khaled Said´s sister conveyed to him her disagreement at such a brutal portrayal of her deceased brother. She felt it was simply debasing the dead. Abu Bakr’s point of view is that to bluntly expose brutality is the most pervasive way of confronting public with reality. Thus, it still remains the most effective way of conveying a message. It is a conscious counter-portrayal to the smiling good-looking face of the Khaled Said stencil that is accompanied with the play of words “Khaled mish Said” “Khaled is not happy”.

The Commodification of Revolutionary Art

If one does a Google search on “graffiti Egypt”, about 10,900,000 results (0,34 second) will emerge. Clearly, since the revolution took place nothing has attracted more the attention of the international press, documentary filmmakers, and the media than graffiti and street art as a new way of claiming public space and the “right to the city”. Revolution Graffiti, Street, Art of the New Egypt by Mia Gröndhal (AUC Press 2013), Wall Talk: Graffiti of the Egyptian Revolution, (Cairo Zeitouna, 2012) are two of the most recent publications to be added to the long list of forthcoming books. Walls of Freedom is another forthcoming book that has already been advertised in al-Ahram online as the most comprehensive book on revolutionary street art. The book is still in the making because the authors managed to raise funds amounting to some six-thousand US dollars from a still needed total of 25 thousand US dollars. The authors claim that they have collected “everything” about graffiti with the collaboration of “50 photographers, 30 artists, and 20 authors to tell the story of the revolution through street art and graffiti.”[xvi] Further funds will be collected through the following measures: “As per the crowd-funding convention, donors will get a set of perks depending on their contribution, including desktop wallpaper, posters, t-shirts, one of the first 100 copies of the book, and an art print and original artworks.”

The posters, art work, hand bags called “pop culture tüte bags”, T shirts, desktop wall paper, and graffiti panels are all advertised on a website.[xvii] One of the most striking “perks” for fundraising for this forthcoming graffiti book has been the sale of the poster of Khaled Said on the Berlin Wall. On this poster, Khaled Said is portrayed as once again the good-looking, neat, middle class young man. Yet it is difficult to oversee the element of commercialization of the revolution with such well intended endeavours. The optimists would read Said´s poster in Berlin as the triumph of globalization or rather internationalization of the revolution. The pessimists on the other hand would perhaps lament transforming martyr Khaled Said into a McDonaldized advertisement branded item.

Martyrs of the Ultra Ahli fans massacre in Port Said. Graffiti in Mohammed Mahmud Street. Captured 1 March 2012/ Image by Mona Abaza

That commodification and commercialization are pervasive in the making of the post-revolution art world, and the international art market has already found lucrative avenues in the Arab World are no news. Definitively the “Arab revolutions” have opened up new market opportunities on a global scale, which will reconsider and elevate the position of “Arab”, “Egyptian”, “Palestinian”, “Bahraini” and “Tunisian” artists. Here the category of nationality much like ethnicity as a form of labelling and distinction seems to be crucial for classification in the art market. It would be naïve to believe commodification could to be avoided.

Conclusion

Since the January 2011 revolution, Egypt witnessed the most violent and dramatic moments through a much-contested transitional phase that was characterised as a “hijacked revolution”. Few would disagree that the violations of human rights and the public display of violence, the killings, the targeted body mutilation of the revolutionaries has reached a peak precisely under the Islamist regime. It is possible to speak today of the making of a collective trauma after the successive massacres of Maspero street, the Ahli football fans in the stadium of Port Said, and the two successive bloody Mohammed Mahmud incidents (2011, 2012) and many other bloody clashes that resulted more than ever in an increasing toll of martyrs. Through echoing the voice of two of the leading graffiti artists, this article attempted to shed the light on the unresolved tensions between the lived, embodied, performative interactions with the walls on the ground with highly moving themes like death and bodily mutilation. These emotions are juxtaposed to the paradox of how the artists end to be seduced or (not) through recognition and through being internationally acclaimed for their art. It seems then that there is no escape from the dilemma of the commodification of art.

But the tensions will remain unresolved since the revolution is not yet over. As long as the blatant violations of human rights, torture and killings continue, as long as the injustices and the economic depression reign with the current corrupt and unaccountable Arab regimes, art (commodified or not) remains a side issue. But the martyrs will keep on appearing and reappearing in the streets as a powerful device of collective consciousness and as a pervasive continuous collective remembrance. Graffiti, public insult and public display of anger remain an effective way of coming to terms with a harsh and draining daily life.

—

Mona Abaza was born in Egypt. She obtained her Ph D. in 1990 in sociology from the University of Bielefeld, Germany. She is currently Professor of Sociology at the American University in Cairo. Between 2009-2011, she was a visiting Professor of Islamology at the Department of Theology, Lund University. She was a visiting scholar in Singapore at the Institute for South East Asian Studies (ISEAS 1990-1992), Kuala Lumpur 1995-96, Paris (EHESS) 1994, Berlin (Fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg 1996-97), Leiden (IIAS, 2002-2003), Wassenaar (NIAS, 2006-2007) and Bellagio (Rockefeller Foundation 2005).

Her books include: The Cotton Plantation Remembered; An Egyptian Family Story, Forthcoming 2013 AUC Press; Twentieth Century Egyptian Art: The Private Collection of Sherwet Shafei, The American University Press, 2011; The Changing Consumer Culture of Modern Egypt, Cairo’s Urban Reshaping, Brill/AUC Press, 2006; Debates on Islam and Knowledge in Malaysia and Egypt, Shifting Worlds, Routledge Curzon Press, UK. 2002; Islamic Education, Perceptions and Exchanges: Indonesian Students in Cairo, Cahier d’Archipel, EHESS, Paris. 1994.

All photos by Mona Abaza, used with permission. All rights reserved

Works Cited:

Mona Abaza. 2012. “Walls, Segregating Downtown Cairo and the Mohammed Mahmud Street Graffiti”, Theory, Culture and Society, 1-18.

Christiane Gruber. 2012. “The Martyrs’ Museum in Tehran: Visualizing Memory in Post- Revolutionary Iran.” Visual Anthropology 25: 68-97.

Sharon Zukin. 1996. “Whose Culture? Whose City ?” In The City Reader, edited by Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout. London: Routledge.

[i] Shounaz Mekky “Slapped Egyptian activist to file case against Brotherhood member “ Al-Arabiya, Wednesday 20 March 2013 .http://english.alarabiya.net/en/2013/03/20/Slapped-Egyptian-activist-to-file-case-against-Brotherhood-member.html

[ii] See youtube Harlem Shake and Other Dances at the Muslim Brotherhood headquarters. www.youtube.com/watch?v=4AXWngXwnqk

[iii] On the same street, see also Mona Abaza’s articles in Jadaliyya. “An Emerging Memorial Space? In Praise of Mohammed Mahmud Street” (10 March 2012), “The Buraqs of Tahrir” (27 May 2012), “The Revolution’s Barometer” (12 June 2012), and “Dramaturgy of a Street Corner (25 January 2013). http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/4625/an-emerging-memorial-space-in-praise-of-mohammed-m; http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/5725/the-buraqs-of-tahrir; http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/5978/the-revolutions-barometer-; http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/9724/the-dramaturgy-of-a-street-corner.

[iv] Not to mention the numerous large marches and various other violent confrontations that took place throughout 2012.

[v] Al-Tahrir newspaper, February, 14, 2013.

[vi] Concerning the significance of Omar Salah ´s case and how it was poorly handled in the media see Amro Ali “The maddening betrayal of potato-seller, Omar Salah”

Open Democracy http://www.opendemocracy.net/amro-ali/maddening-betrayal-of-potato-seller-omar-salah

[vii] I took a photograph of Omar Salah´s portrait in February 2013.

[viii] Published by Dar al-ain lil-nashr, 2013

[ix] A buraq is a mythological figure, described as a creature from the heavens that transports prophets. On the buraqs of Tahrir, see also Mona Abaza http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/5725/the-buraqs-of-tahrir;

[x] The interpretation of Alaa Awad´s work draws on the author’s interviews as well as the documentary “The Art of Narrating the Egyptian Revolution, An Interview with Alaa Awad.“ Film by Rudolf Thome, Jadaliyya April 18, 2012, 2012. http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/5134/the-art-of-narrating-the-egyptian-revoltion_an-in

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Personal communication with Ammar Abu Bakr, 19 May 2013.

[xiii] Ammar Abu Bakr has exhibited his art in Beirut. He seems to make a difference between exhibiting art in galleries and reproducing graffiti for galleries.

[xiv] See Mona Abaza. “The Violence of the Counter-Revolution.” Global Dialogue Volume 3, 3 May 2013.

[xv] Hazem Kandil “Deadlock in Cairo” London Review of Books, LRB 21 March 2013, http://www.lrb.co.uk/v35/n06/hazem-kandil/deadlock-in-cairo

[xvi] Ahram online “Crowd-Funding Campaign Supports Book on Egypt’s Graffiti” Ahram Online, Thursday 6 June 2013

[xvii] http://www.indiegogo.com/projects/walls-of-freedom

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Pipelines and Politics: Natural Gas Connects Israel and Egypt

- Egypt and the Syrian Refugee Crisis

- Trajectories of Anticolonialism in Egypt

- When Military Coups d’état Become Acts of Social Justice

- Theory Synthesis in Sport and International Relations Research

- Opinion – Dictatorships Are Unstable, Yet the International System Continues to Support Them